In order to best understand root functions, you should know how to use rational exponents (like $x^{1/2}$), and you should know what they mean: Rational and negative exponents

You should also be adept with the laws of exponents, given in the same section. You can download a table of the laws of exponents here.

You should also be familiar with the function concept and domain & range.

Review of rational & negative exponents

Rational exponents

This is a quick review of rational and negative exponents. You can learn about them in more detail here. Recall that a rational number is a ratio of integers, like ½ or ¾. In general, for a rational function,

$$f(x) = x^{\frac{a}{b}},$$

$a$ is the power and $b$ is the root of $x$. $x^{a/b}$ means "Take the $b^{th}$ root of $x$ raised to the $a$ power," OR "raise the $b^{th}$ root of $x$ to the power of $a$."

We can think of these in terms of the laws of exponents:

$$x^{\frac{a}{b}} = (x^a)^{\frac{1}{b}} = ( x^{\frac{1}{b}} )^a$$

Here are a couple of examples:

$$16^{\frac{3}{4}} = \left( 16^{\frac{1}{4}} \right)^3 = 2^3 = 8$$

$$25^{\frac{3}{2}} = \left( 25^{\frac{1}{2}} \right)^3 = 5^3 = 125$$

Negative exponents

First, by definition,

$$x^{-1} = \frac{1}{x}$$

Now by using the laws of exponents, we see that any negative exponent means, "keep the positive power and take the reciprocal." Here are a few examples:

$$ \begin{align} x^{-2} &= (x^2)^{-1} = (x^{-1})^2 = \left( \frac{1}{x} \right)^2 = \frac{1}{x^2} \\[5pt] x^{-\frac{1}{3}} &= \left( x^{\frac{1}{3}} \right)^{-1} = (x^{-1})^{\frac{1}{3}} = \frac{1}{x^{1/3}} \end{align}$$

Now that's a lot of equal signs, but do stare at those for a minute to convince yourself that they're all true. If you can write these expressions in these several ways, you'll know all you need to know about negative exponents.

Just for review, here is a table of the laws of exponents.

Laws of exponents

| Law | Rule |

|---|---|

| Product | $x^m \cdot x^n = x^{m + n}$ |

| Quotient | $\frac{x^m}{x^n} = x^{m - n}$ |

| Power | $(x^m)^n = x^{m \cdot n}$ |

| Reciprocal | $x^{-1} = \frac{1}{x}$ |

| Identity | $x^0 = 1$ |

Power vs. root functions

Any function $f(x) = x^n,$ with $n \gt 1,$ is called a power function (also a polynomial function with one term), and a function $f(x) = x^{1/n},$ where $n \gt 1$ is a root function. More generally,

$$ \begin{align} x^{\frac{a}{b}} &= \text{a root function} \text{ if } a \lt b\\[5pt] x^{\frac{a}{b}} &= \text{a power function} \text{ if } a \gt b\\[5pt] \end{align}$$

Four functions are plotted in the graph here. $f(x) = x^3$ and $g(x) = x^2$ are power functions (a quadratic and a cubic), with graphs that should be familiar (only part of the domain, [0, 3] is shown). The root functions $h(x) = x^{1/2}$ and $k(x) = x^{1/3}$ are actually inverses of f(x) and g(x), respectively, so their graphs have mirror symmetry across the line $y = x$. These are the general shapes of root function graphs. We might consider $k(x) = x^{1/2}$ to be the parent of all root functions.

Graphs and transformations

We want to get good at visualizing or sketching the graphs of root functions. Just like any function class, our goal here is to sketch out the basic shape of the function graph, including some key points. It's not to be able to produce an accurate drawing of the function. That's what computers are for. We just want to be able to recognize when the computer-drawn function can't be right because of some input error — it happens all the time.

Even & odd rational roots

There is a fundamental difference in root-function graphs in which the denominator of the rational exponent is even or odd. Below the functions $f(x) = x^{\frac{1}{2}}$ and $g(x) = x^{\frac{1}{3}}$ are drawn. Notice that the domain of the square-root function is $[0, \infty)$, but the domain of the cube-root function is $(-\infty, \infty).$ That's generally true for root functions, but can be less clear when the exponent is a decimal or non-rational number.

Transformations

The fundamental function transformations of root functions are the same as those for any function. Remember that we can translate, stretch and compress any function in four ways by writing f(x) as

$$f(x) \rightarrow A \cdot f \left( \frac{x}{c} - h \right) + k,$$

where $A, \; c, \; h$ and $k$ are vertical stretching, horizontal stretching, horizontal and vertical translation parameters, respectively. We can write a general root function like this:

$$f(x) = A \left( \frac{x}{c} - h \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} + k,$$

where:

- $n$ is the root: 2 = square root, 3 = cubed root, and so on, and n doesn't have to be an integer.

- $A$ is the vertical scaling parameter; $A \gt 1$ stretches the function vertically, $0 \lt A \lt 1$ compresses it vertically, and if $A \lt 0$, the function is flipped upside down.

- $c$ is the horizontal scaling parameter; $0 \lt c \lt 1$ compresses the function horizontally, $c \gt 1$ stretches the function horizontally, and if $c \lt 0$, the function is flipped across the $y$-axis.

- $h$ is the horizontal translation parameter; $h \gt 0$ means a shift to the right and $h \lt 0$ means a shift to the left by $h$ units. Notice that the function is defined with a minus operation in the parentheses.

- $k$ is the vertical translation parameter; $k \gt 0$ is a translation upward and $k \lt 0$ is a downward translation.

Below are a few graphical examples of each kind of transformation. Be sure to stare at each graph to make sure it makes sense to you. Here I've just used a square-root function as the parent function, and that is sketched on each plot in black for reference.

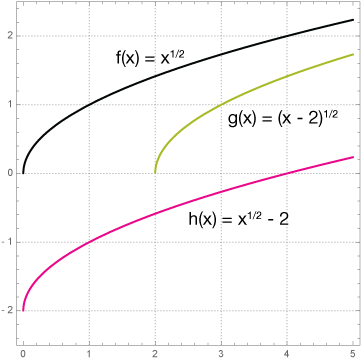

Below, three functions are plotted: $f(x) = x^{\frac{1}{2}},$ $g(x) = (x - 2)^{\frac{1}{2}},$ and $h(x) = x^{\frac{1}{2}} - 2.$ Notice that $f(x)$ is the parent function of square-root functions (just the simplest example), $g(x)$ is that same function translated by two units to the right $(h = 2)$, and $h(x)$ is that parent translated downward by two units.

The plot below shows a couple of vertical-scaling transformations. In this case the parent function is plotted along with a version (g(x)) that is scaled (stretched) vertically by a factor of two and $h(x) = -x^{\frac{1}{2}},$ which is flipped across the $x$-axis. Notice that if we combine f(x) and h(x), we get a function $k(x) = ±x^{\frac{1}{2}},$ which is a sideways-opening parabola.

The graph below illustrates how horizontal stretching affects root-function graphs. $f(x) = x^{1/2}$ is the parent function. $g(x) = (x/0.5)^{1/2}$ is the same graph compressed horizontally by a factor of $\sqrt{2}.$ It's $\sqrt{2}$ because the horizontal stretching parameter is inside the root function. $h(x) = (x/2)^{1/2}$ is the parent graph stretched horizontally by a factor of $\sqrt{2}.$

Example 1

Sketch the graph of $g(x) = \frac{1}{2} (x + 3)^{\frac{1}{2}} - 2.$

$$f(x) = A \left( \frac{x}{c} - h \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} + k$$

Now we can see that for our graph:

- $h = -3$, so the whole graph is translated three units to the left.

- $k = -2$, so the whole graph is also translated two units downward. These first two transformations lead to a graph that starts at coordinates (-3, 2).

- Finally, $A = \frac{1}{2}$, so the whole graph is compressed vertically by a factor of two, which we only need to indicate by shortening it. It's not important to plot points and draw a precise graph. That's what computers are for.

Example 2

Sketch the graph of $g(x) = 2 (x - 2)^{\frac{1}{2}} - 3.$

The graph shows red arrows indicating the two translations. The gray dashed curve is the parent function, $f(x) = x^{1/2},$ without the vertical scaling. The magenta curve is the final sketch of the function.

It's often best to sketch graphs like this one as we've done here, in a step-by-step fashion, so that each step makes sense before you move ahead.

Example 3

Sketch the graph of $g(x) = \left(\frac{x}{4} - 1 \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} - 2.$

Now at a first look, we might expect that the $(0, \; 0)$ point of the parent function (black curve) should just be moved one unit to the right and two down, but it actually moves to position $(4,\; -2)$. What gives?

To understand what's going on with this set of transformations, let's begin with the original function:

$$f(x) = \left( \frac{x}{4} - 1 \right)^{1/2} - 2$$

Now we'll get a common denominator inside the parentheses, then factor out a ¼.

$$ \begin{align} f(x) &= \left( \frac{x}{4} - \frac{4}{4} \right)^{1/2} - 2 \\[5pt] &= \left[ \frac{1}{4} (x - 4)\right]^{1//2} - 2 \\[5pt] &= \frac{1}{2} (x - 4)^{1/2} - 2 \end{align}$$

In the last step above we just took the square root of ¼ and moved the result, ½, outside of the main root function.

Now we have a function form that looks like our graph. It's translated 4 units to the right, 2 downward, and it has been compressed vertically (compare to the dashed gray curve) to ½ of its previous height. Vertical compression is the same as horizontal stretching, which is what we'd expect for the parameter $c = 4$ in the original function.

The lesson here is to be careful about all horizontal scaling transformations. Because that parameter $(c)$ is inside of the main part of the function (the root, in this case), it gets changed by the function.

![]()

xaktly.com by Dr. Jeff Cruzan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. © 2012-2025, Jeff Cruzan. All text and images on this website not specifically attributed to another source were created by me and I reserve all rights as to their use. Any opinions expressed on this website are entirely mine, and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of my employers. Please feel free to send any questions or comments to jeff.cruzan@verizon.net.